The Problem with Fair Trade Coffee

By Colleen Haight

Summer 2011

Stanford Social Innovation Review

Peter Giuliano is in many ways the model of a Fair Trade coffee advocate. He began his career as a humble barista, worked his way up the ladder, and in 1995 co-founded Counter Culture Coffee, a wholesale roasting and coffee education enterprise in Durham, N.C. In his role as the green coffee buyer, Giuliano has developed close working relationships with farmers throughout the coffee-growing world, traveling extensively to Latin America, Indonesia, and Africa. He has been active for more than a decade in the Specialty Coffee Association of America, the world’s largest coffee trade association, and currently serves as its president.

Giuliano originally embraced the Fair Trade-certification model—which pays producers an above-market “fair trade” price provided they meet specific labor, environmental, and production standards—because he believed it was the best way to empower growers and drive the sustainable development of one of the world’s largest commodities. Today, Giuliano no longer purchases Fair Trade-certified coffee for his business. “I think fair trade as a concept is very relevant,” says Giuliano. But “I think the Fair Trade-certified FLO model is not relevant at all and kind of never has been, because they were doing something different than they were selling to the consumer. … That’s exactly why I left TransFair [now Fair Trade USA]. They’re selling a different thing than they’re producing.”

Giuliano is among a growing group of coffee growers, roasters, and importers who believe that Fair Trade-certified coffee is not living up to its chief promise to reduce poverty. Retailers explain that neither FLO—the Fairtrade Labelling Organizations International umbrella group—nor Fair Trade USA, the American standards and certification arm of FLO, has sufficient data showing positive economic impact on growers. Yet both nonprofits state that their mission is to “use a market-based approach that empowers farmers to get a fair price for their harvest, helps workers create safe working conditions, provides a decent living wage, and guarantees the right to organize.”1 (In this article, the term Fair Trade coffee refers to coffee that has been certified as “Fair Trade” by FLO or Fair Trade USA; the term Fair Trade refers to the certification model of FLO and Fair Trade USA; and the term fair trade refers to the movement to improve the lives of growers and other producers through trade.)

FLO rules cover artisans and farmers who produce not just coffee but also a variety of goods, including tea, cocoa, bananas, sugar, honey, rice, flowers, cotton, and even sports balls. Its certification process requires producing organizations to comply with a set of minimum standards “designed to support the sustainable development of small-scale producers and agricultural workers in the poorest countries in the world.” 2 These standards—31 pages of general and product-specific standards—detail member farm size, electoral processes and democratic organization, contractual transparency and reporting, and environmental standards, to name only a few. Supporting organizations, such as Fair Trade USA, in Oakland, Calif., ensure that the product is properly handled, labeled, and marketed in the consuming country.

Like many economic and political movements, the fair trade movement arose to address the perceived failure of the market and remedy important social issues. As the name implies, Fair Trade has sought not only to protect farmers but also to correct the legacy of the colonial mercantilist system and the kind of crony capitalism where large businesses obtain special privileges from local governments, preventing small businesses from competing and flourishing. To its credit, Fair Trade USA has played a significant role in getting American consumers to pay more attention to the economic plight of poor coffee growers. Although Fair Trade coffee still accounts for only a small fraction of overall coffee sales, the market for Fair Trade coffee has grown markedly over the last decade, and purchases of Fair Trade coffee have helped improve the lives of many small growers.

Despite these achievements, the system by which Fair Trade USA hopes to achieve its ends is seriously flawed, limiting both its market potential and the benefits it provides growers and workers. Among the concerns are that the premiums paid by consumers are not going directly to farmers, the quality of Fair Trade coffee is uneven, and the model is technologically outdated. This article will examine why, over the past 20 years, Fair Trade coffee has evolved from an economic and social justice movement to largely a marketing model for ethical consumerism—and why the model persists regardless of its limitations.

THE ORIGINS OF FAIR TRADE

The idea of fair trade has been around since people first started exchanging goods with one another. The history of trade has shown, however, that exchange has not always been fair. The mercantile system that dominated Western Europe from the 16th to the late 18th century was a nationalistic system intended to enrich the state. Businesses, such as the Dutch East India Company, operating for the benefit of the mother country in “the colonies,” were afforded monopoly privileges and protected from local competition by tariffs. Under these circumstances, trade was anything but fair. Local workers often were compelled through force—slavery or indentured servitude—to work long hours under terrible conditions. In the 1940s and 1950s, nongovernmental and religious organizations, such as Ten Thousand Villages and SERRV International, attempted to create supply chains that were fair to producers, mostly creators of handicrafts. In the 1960s, the fair trade movement began to take shape, along with the criticism that industrialized countries and multinational corporations were using their power for further enrichment to the detriment of poorer counties and producers, particularly of agricultural products like coffee.

Adding to these perceived economic imbalances is the cyclical nature of the coffee business. As an agricultural product that is sensitive to growing conditions and temperature fluctuations, coffee is subject to exaggerated boom-bust cycles. Booms occur when farm output is low, causing price increases due to limited supply; bust cycles occur when there is a bumper crop, causing price declines due to large supply. Price stabilization is an objective commonly sought by less-developed countries through commodity agreements. Thus the International Commodity Agreement (ICA) evolved as a means to stabilize the chronic price fluctuations and endemic instability of the coffee industry. The first of these agreements arose in the 1940s to provide stability during wartime, when the European markets were unavailable to Latin American producers.

After the war, a boom in coffee demand made renewal of the agreement unnecessary. But during the late 1950s, down cycles threatened economies once again. The ICA essentially was little more than a cartel agreement between the member countries (coffee producers) to restrict output during bust periods to maintain higher prices, storing the surplus beans to sell later when output was low. Because the US government was concerned about the spread of communism in Latin America, it supported the cartel by enforcing import restrictions. In 1989, however, with the fall of the Berlin Wall and the waning of communist influence, the United States lost interest in supporting the agreement and withdrew. Without US enforcement, the cartel fell prey to rampant cheating on the part of its members and eventually dissolved. Attempts have since been made to resurrect the cartel—but though it exists in name, it remains largely ineffective.

Recognizing the dire circumstances confronting farmers during the late 1980s, when the price of coffee once again plunged, fair trade activists formulated a system whereby farmers could obtain access to international markets and reasonable reward for their labor. In 1988 a coalition of those economic justice activists created the first fair trade certification initiative in the Netherlands, called Max Havelaar, after a fictional Dutch character who opposed the exploitation of coffee farmers by Dutch colonialists in the East Indies. The organization created a label for products that met certain wage standards. Other similar organizations arose within Europe, eventually merging in 1997 to create FLO, based in Bonn, Germany, which today sets the Fair Trade-certification standards and serves to inspect and certify the producer organizations.

ETHICAL CONSUMERISM

Why do we care about fairly traded coffee? One reason is the importance of coffee to the economies of the countries in which the crop is grown. Coffee is the second most valuable commodity exported from developing countries, petroleum being the first. For many of the world’s least developed countries, such as Honduras, Ethiopia, and Guatemala, coffee exports make up an enormous share of the export earnings, comprising in some cases more than 50 percent of foreign exchange earnings.3 In addition, many of the coffee growers are small and their businesses are financially marginal.

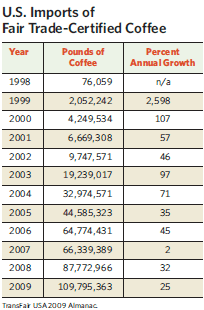

Although some of the world’s poorest countries produce coffee, the preponderance of that production is consumed by the citizens of the world’s wealthiest countries. The United States is the world’s single largest consuming country, buying more than 22 percent of world coffee imports; the combined countries of the European Union import roughly 67 percent, 4 with other countries importing the remaining 10 percent. According to the Specialty Coffee Retailer, an industry resource site, specialty coffee in 2010 accounted for $13.65 billion in sales, one-third of the nation’s $40 billion coffee industry. The Specialty Coffee Association of America reports that approximately 23 million people in the United States drink specialty or gourmet coffee daily. Fair Trade coffee, which has grown steadily from 76,059 pounds in 1998 to 109,795,363 pounds in 2009,5 constitutes only about 4 percent of that $14 billion market.

The primary way in by which FLO and Fair Trade USA attempt to alleviate poverty and jump-start economic development among coffee growers is a mechanism called a price floor, a limit on how low a price can be charged for a product. As of March 2011, FLO fixed a price floor of $1.40 per pound of green coffee beans. FLO also indexes that floor to the New York Coffee Exchange price, so that when prices rise above $1.40 per pound for commodity, or non-specialty, coffee, the Fair Trade price paid is always at least 20 cents per pound higher than the price for commodity coffee.

Commodity coffee is broken into grades, but within each grade the coffee is standardized. This means that beans from one batch are assumed to be identical to those in any other batch. It is a standardized product. Specialty coffee, on the other hand, is sold because of its distinctive flavor characteristics. Because specialty coffees are of a higher grade, they command higher prices. Fair Trade coffee can come in any quality grade, but the coffee is considered part of the specialty coffee market because of its special production requirements and pricing structure. It is these requirements and pricing structure that create a quality problem for Fair Trade coffee.

To understand how the problem arises, one must understand that the low consumer demand for Fair Trade coffee means that not all of a particular farmer’s coffee, which will be of varying quality, may be sold at the Fair Trade price. The rest must be sold on the market at whatever price the quality of the coffee will support.

A simple example illustrates this point. A farmer has two bags of coffee to sell and there is a Fair Trade buyer for only one bag. The farmer knows bag A would be worth $1.70 per pound on the open market because the quality is high and bag B would be worth only $1.20 because the quality is lower. Which should he sell as Fair Trade coffee for the guaranteed price of $1.40? If he sells bag A as Fair Trade, he earns $1.40 (the Fair Trade price) and sells bag B for $1.20 (the market price), equaling $2.60. If he sells bag B as Fair Trade coffee he earns $1.40, and sells bag A at the market price for $1.70, he earns a total of $3.10. To maximize his income, therefore, he will choose to sell his lower quality coffee as Fair Trade coffee. Also, if the farmer knows that his lower quality beans can be sold at $1.40 per pound (provided there is demand), he may decide to increase his income by reallocating his resources to boost the quality of some beans over others. For example, he might stop fertilizing one group of plants and concentrate on improving the quality of the others. Thus the chances increase that the Fair Trade coffee will be of consistently lower quality. This problem is accentuated when the price of coffee rises to 30-year highs, as it has done recently.

One of the unique characteristics of the FLO and Fair Trade USA model is that only certain types of growers can qualify for certification—specifically, small growers who do not rely on permanent hired labor and belong to democratically run cooperatives. This means that private estate farmers and multinational companies like Kraft or Nestlé that grow their own coffee cannot be certified as Fair Trade coffee, even if they pay producers well, help create environmentally sustainable and organic products, and build schools and medical clinics for grower communities.

Although the cooperative requirement may seem unusual, it follows logically from the experience of Paul Rice, founder and president of Fair Trade USA. Rice spent most of the early 1980s working with cooperative farmers in Latin America, studying and implementing training programs for small farmer organizations on behalf of the Nicaragua Agrarian Reform Ministry under the Sandinista administration. In 1990, he became the first CEO of prodecoop, a fair trade organic cooperative representing almost 3,000 small coffee farmers in northern Nicaragua. Then in 1998, he founded Fair Trade USA. Rice sees cooperatives as the key to the empowerment of the independent coffee farmer, providing a union-like type of collective bargaining power that enables cooperative leaders to negotiate pricing for the individual members.

Membership in a cooperative is a requirement of Fair Trade regulations. Another core element is the premium—the subsidy (now 20 cents per pound) paid by purchasers to ensure economic and environmental sustainability. Premiums are retained by the cooperative and do not pass directly to farmers. Instead, the farmers vote on how the premium is to be spent for their collective use. They may decide to use it to upgrade the milling equipment of a cooperative, improve irrigation, or provide some community benefit, such as medical or educational facilities.

Fair Trade USA is a nonprofit, but an unusually sustainable one. It gets most of its revenues from service fees from retailers. For every pound of Fair Trade coffee sold in the United States, retailers must pay 10 cents to Fair Trade USA. That 10 cents helps the organization promote its brand, which has led some in the coffee business to say that Fair Trade USA is primarily a marketing organization. In 2009, the nonprofit had a budget of $10 million, 70 percent of which was funded by fees. The remaining 30 percent came from philanthropic contributions, mostly from foundation grants and private donors.

People in the coffee industry find it hard to criticize FLO and Fair Trade USA, because of its mission “to empower family farmers and workers around the world, while enriching the lives of those struggling in poverty” and to create wider conditions for sustainable development, equity, and environmental responsibility.6 “I’m hook, line, and sinker for the Fair Trade mission,” says Shirin Moayyad, director of coffee purchasing for Peet’s Coffee & Tea Inc. “When I read [the statement], I thought, there’s nothing I disagree with here. Everything here I believe in.” Yet Moayyad has concerns about the effectiveness of the model, mostly because she does not see FLO making progress toward those goals.

Whole Foods Market initially rejected the Fair Trade model. The supermarket chain only recently began buying Fair Trade coffee, through its private label coffee, Allegro, in response to the demand from their consumers. Jeff Teter, president of Allegro Coffee, a specialty coffee business begun in 1985 and sold to Whole Foods in 1997, said that his main concern has been the quality of Fair Trade coffee. “To get great quality coffee, you pay the market price. Now, in our instance, it’s a lot more than what the Fair Trade floor prices are,” he says. As for social justice for coffee growers, Teter responds: “We were living the model at least 10 years before Paul Rice and TransFair people got started here in America. … Paul Rice and his group have done an amazing job convincing a small group of vocal and active consumers in America to be suspicious of anybody who isn’t FT.” Rice disagrees, arguing, “Fair Trade is the only certification program today that ensures and proves that farmers are getting more money.”

AN IMPERFECT MODEL

My field and analytical research has found that there are distinct limitations to the Fair Trade model.7 Perhaps the most serious challenge is the extraordinarily high price of coffee. “The market today is five times higher than when FLO entered the United States. The market’s at $2.50 (per pound for commodity coffee) today vs. the 40 cents or 50 cents (per pound) it was at in 2001,” says Dennis Macray, former director of global sustainability at Starbucks Coffee Co. This price shift dampens farmers’ desire to sell their high-quality coffee at the Fair Trade price. Many co-ops, according to Macray, are choosing to default on the Fair Trade contracts, so that they can do better for their members by selling on the open market. Macray, who is now an independent sustainability consultant with clients such as the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, says the default problem is seriously compounded by the perceptions of quality. Some roasters express concern that the quality of Fair Trade coffee is not at the same high levels as other types of specialty coffee sold alongside it. “For some cooperatives the Fair Trade price became the ceiling, not the floor. … Many Fair Trade buyers do not see a reason why they should pay any more than the fair trade price for the value that is Fair Trade,” explains Macray.

In the past, coffee growers were often isolated in remote regions and had little access to market information on the value of their product. Unscrupulous buyers might offer only very low prices, taking advantage of farmers’ lack of information. Today, however, growers have access to coffee price fluctuations on their cell phones and, in many cases, have a keener understanding of how to negotiate with foreign distributors to get the best price per pound. In addition, the growing demand for very high quality coffee has led to a tremendous increase in the number of buyers traveling to more remote regions to ensure the supply they require.

Another important flaw is FLO’s inability to alter the circumstances of the poorest of the poor in the coffee farming community. Although FLO does dictate certain minimal labor standards, such as paying workers minimum wage and banning child labor, the primary focus and beneficiary is the small farmer, who, in turn, is defined as a small landowner. The poorest segment of the farming community, however, is the migrant laborer who does not have the resources to own land and thus cannot be part of a cooperative. In Costa Rica, for example, most small farms, including those selling Fair Trade coffee, employ migrant laborers for harvesting, particularly from Nicaragua and Panama. Rice believes that because the “yields are so low on a small farm and it’s basically family run, the migrant labor issue is not as relevant.” But at the same time he admits that the benefits of Fair Trade do not reach migrant laborers; he says he wants to expand the model to serve this population.

Rice has never wavered from his view that Fair Trade’s “central goal is to alleviate poverty,” and he is adamant that the organization’s model is as relevant as it was 20 years ago. But during that time many of FLO’s provisions of have become duplications of regulations already in place in Latin American countries, such as minimum wage requirements, credit financing, and contracting terms. “I just don’t think that the benefits are trickling down,” says Philip Sansone, president and executive director of the Whole Planet Foundation (the philanthropic arm of Whole Foods). Rice disagrees and defends his model. “The small holders in Latin America would have no way of climbing out of poverty,” he says. “One-acre farmers standing alone are pretty much always going to be victimized by stronger market forces, be they middlemen or moneylenders. At those farm unit sizes and yields, no one is viable in the global market if they stand alone.”

Another challenge for FLO is the issue of transparency in business dealings. FLO regulations require a great amount of record keeping, to ensure that individual farmers have access to all information pertaining to the cooperative’s sales and farming practices, enabling them to make more informed business and agricultural decisions. But this record keeping has proven to be a hurdle in some cases. In addition to being time-consuming, it has also raised language and literacy barriers. Certification forms, for example, only recently were made available in Spanish. “They want a record to be kept of every daily activity, with dates and names, products, etc. They want everything kept track of. The small producers, on the other hand, can hardly write their own name,” 8 said Jesus Gonzales, a farmer at Tajumuco Cooperative in Guatemala. Records kept by cooperatives have shown that premiums paid for Fair Trade coffee are often used not for schools or organic farming but to build nicer facilities for cooperatives or to pay for extra office staff. Gerardo Alberto de Leon, manager of Fedecocagua, the largest cooperative in Guatemala selling Fair Trade coffee, told me during my 2006 field research, “The premium we use here [at the cooperative]—you saw our coffee lab, it is very professional.”

Although the cooperative lab may improve quality or sales or aid in member education, it is not necessarily where consumers who buy Fair Trade coffee think their money is going. Macray says coffee consumers want to know that the extra premiums are being used for social services. “Many licensees have started to question whether the premiums were being used for social good: schools, education, health, nutrition, and so on,” he says. “It became difficult to tell the story of where that premium was going. So in your retail shop, you want to be able to tell your customers, yeah, how we provide all this extra funding for these co-ops and it made these differences.”

FLO also provides incentives for some farmers to remain in the coffee business even though the market signals that they will not be successful. If a coffee farmer’s cost of production is higher than he is able to obtain for his product, he will go out of business. By offering a higher price, Fair Trade keeps him in a business for which his land may not be suitable. There are areas all over Latin America and Africa where the climate and growing conditions are simply not conducive to coffee growing. “Fair Trade directs itself to organizations and regions where there is a degree of marginality,” explains Eliecer Ureña Prado, dean of the School of Agricultural Economics at the University of Costa Rica. “We’re talking about unfavorable climates [for coffee production]. … Regions that are not competitive.”

THE FUTURE OF FAIR TRADE COFFEE

The FLO model has changed little since its inception. Although the Fair Trade price and premium for coffee has been adjusted upward over time, the rules and regulations have remained fairly static. Fair Trade’s chief legacy may be greater consumer awareness among coffee drinkers. “We generate awareness to create demand in the market,” explains Stacy Wagner, public relations manager at Fair Trade USA. And they have had tremendous success doing so. Today, according to Wagner, 50 percent of American households are aware of Fair Trade coffee, up from only 9 percent in 2005.

Representatives from Starbucks, Peet’s, and Green Mountain Coffee Roasters (which owns such brands as Caribou Coffee, Tully’s, and Newman’s Own) all report a push from consumers for more transparency of contract and socially responsible business practices. It is rare to find a coffee roaster or retailer these days that does not address social issues in some way. Some do so by offering Fair Trade coffee. Others, however, have sought out other solutions, such as adopting other certifications or by developing their own programs. “A number of importers and exporters in the coffee business are saying we can get more money into the pockets of farmers through direct trade than if we use the FLO model,” says Macray.

Examples of businesses that have risen to meet consumer demands include Starbucks, Peet’s, and Whole Foods’ Allegro coffee. Although Starbucks offers Fair Trade coffee as one of a number of options, they also have put into place a C.A.F.E. Practice—a program that defines socially responsible business guidelines for their buyers. Many coffee producers have taken note of this model and made their practices more sustainable to attract the attention of Starbucks’ buyers. Likewise, Peet’s buys a lot of coffee from TechnoServe, an organization working to improve the business practices of farmers in developing countries. “One of the objections to Fair Trade could be that the term ‘cooperative’ doesn’t perforce equate to ‘farmer,’” says Moayyad. “Just because a certain price is guaranteed to the cooperative, doesn’t actually mean that the farmer is receiving it.”

With TechnoServe, farmers get a much higher percentage of the proceeds—up to 60 percent more according to Moayyad, even though their stated focus is “developing entrepreneurs, building businesses and industries, and improving the business environment.” 9 TechnoServe’s model focuses on quality production and farm management. “It’s not a charity,” says Jim Reynolds, roast master emeritus of Peet’s, who has more than 30 years of buying experience. “It’s building skills and better business organization, so they can run their own co-ops more efficiently and earn better pricing by finding good buyers.” Teter also follows this type of socially responsible corporate investment. Allegro pays well above the Fair Trade price to obtain the quality coffees its customers want. In addition, 5 percent of Allegro’s profits goes to charity, and 85 percent is spent in growers’ communities.

“The model for sustainable coffee that was popular five years ago has changed quite a bit,” says Macray. “Five years ago, it was common practice to just go out and buy certified coffees and check the box; and today it’s about integrating sustainability and transparency into your supply chain. Companies are making it a core way of doing business.”